The Archbishop of Canterbury, in order to prevent schism, dancing to the tune of bigoted African bishops and fanatical evangelists on the subject of homosexuality and the church, has proved a grotesque spectacle and made a monkey out of the Primate of All England.

Under the headline “Stand up, Archbishop, and tell the gay bashers where to go”, A A Gill brilliantly summed it up in the Sunday Times recently: “The Archbishop of Canterbury is bending over backwards to placate the rabid homophobes of the born again charismatic wing of the church in the belief that cohesion is more important than conscience. He knows what we all know, that gayness is not a sin, it's not even a faux pas. It is the way some people are, but to placate a sordid, spiritually bereft prejudice he will go halfway round the world to search out mendacious phrases to keep the church one big, unhappy, sniggerable communion.”

A fascinating subject then for a bit of agitprop theatre and with Love the Sinner, playwright Drew Pautz doesn't disappoint, with a taughtly-crafted drama in which scene after scene crackles with tension and intention.

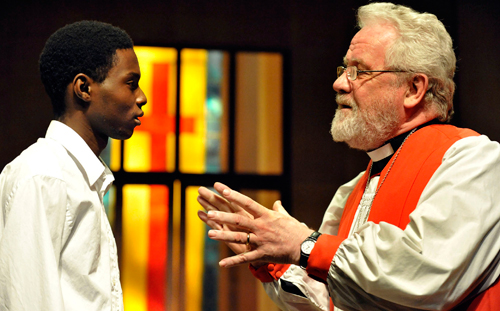

It's a trail-blazing debut by a fresh-out-of-ALRA Fiston Barek as Joseph

At rise a conclave of Anglican archbishops are holed up in an African hotel conference room where deciding on coffee or tea is marginally less protracted than the subject of leaving the gays alone to do what they do with everyone's blessing. As sweat beads fall and tempers fray there's no air conditioning in the room and no air in the debate. I would love to tell you what happens next but prior knowledge of this always fascinating plot will spoil it. Very soon the debate moves from the arguments of ethics in the conference room to issues of a more personal level in the bedroom.

It's a trail-blazing debut by a fresh-out-of-ALRA Fiston Barek as Joseph, whose predicament provides the metaphor for the wider argument and an emotionally powerful dénouement. His mix of wit, wry deception, open sincerity, sweetness and menace combine in a performance of staggering flair and maturity that keeps you guessing all evening.

Barek is matched by the other points of this triangle Jonathan Cullen and Charlotte Randle as husband and wife Michael and Shelley. Their domestic scenes are pitch perfect and an abject lesson in, amongst other things, how intensity is heightened by not making heavy weather of it. Cullen and Randle captivate with such complete connection to the material.

Sure whether it's air-conditioning, tea trays, families of squirrels or Helen of Troy, the metaphors are almost as clunky as the set. But I guess with a modern morality parable that's intentional and certainly it's part of the fun – the metaphors bulldozing their way in not the set trucks.

Credulity might be stretched too but show me a parable where that doesn't happen, however, if ever there was a play with licence to graphically depict the great joys to be gained from vigorous gay sex this was it. Instead this love dares to speak it's name here but not show it's face.

When Michael is finally stripped bare (Metaphor! Whoop! Whoop!) it's after a hetero not homo clinch. So it's safe for Rowan Williams to see and so he should particularly as the poor man was reportedly perfectly gay-friendly before being burdened with the top job.

Last word to A A Gill: “Which of us wants to get married, baptise the children or be eulogised by people who think of little else but others' bottoms, and not in a nice way?”

Be the first to comment